The Unspoken Hierarchy of Genres

January 26, 2026

What is the “genre hierarchy” in Indian language publishing?

It’s the informal ranking of genres by cultural status—where poetry and literary fiction are treated as “serious,” while romance, pulp, devotional and mass fiction may sell more but get less respect.

Why is poetry considered higher status than romance or thrillers?

Because awards, academic validation, and elite cultural institutions have historically defined “good literature” around difficulty, experimentation, and social realism—traits more associated with poetry and literary fiction.

Which genres sell the most in Indian languages?

Mass genres like romance, crime/thriller, devotional retellings, and practical nonfiction often have wider readership. Educational publishing is a dominant economic force overall.

Is pulp fiction important for Indian languages?

Yes. It builds habitual readers at scale. Hindi pulp authors have historically sold extremely high volumes, and writers like Surender Mohan Pathak have demonstrated sustained commercial readership.

Is the hierarchy changing?

Yes - audio, digital discovery, and shifting reader cohorts are making popular genres more visible, while measured market signals show strong momentum for fiction in India.

Walk into a serious literary gathering in India, say, a book launch in Hindi, Marathi, Malayalam, Bangla, and mention you write romance. Watch the room do a tiny internal rearrangement.

Not outwardly. Nobody is rude. But something shifts.

If you say you write poetry, you’ll get an extra half-second of attention, a respectful nod, maybe even a “wah.”

If you say you write short stories, you’ll be asked who you “read seriously.”

If you say you write crime thrillers, you’ll be asked whether you’re “planning to move to something more literary.”

And... if you say you write devotional retellings or relationship fiction that sells like hot samosas at a railway station bookstall—well, you’ll be congratulated in the tone people reserve for a cousin who has chosen a “safe job.”

This isn’t about one language. It’s a structure that repeats across Indian languages, with local variations. A quiet genre ladder: some genres are treated as culturally superior, some as commercially useful, and some as faintly embarrassing, even when they pay the bills.

The Ladder: Who Gets Prestige, Who Gets Sales, Who Gets Ignored

Most Indian language ecosystems have a “prestige shelf” and a “money shelf,” and they aren’t the same shelf.

The prestige shelf (high status, lower volume)

- Poetry

- Literary fiction (especially “serious” realism, social novels, experimental work)

- Short stories (the genre of editors and juries)

- Essays, criticism, memoir (selectively—depending on author profile)

The respectable middle (status varies by author, can sell decently)

- Children’s books (often respected, but underfunded)

- History, biography (especially political/cultural)

- Translations of “important” works (classics, award-winners)

The mass shelf (big volumes, low prestige)

- Romance, relationship fiction, “family novels”

- Crime/thriller, detective series, pulp

- Mythological/devotional retellings (often huge readership)

- Self-help in regional voice (massive in many belts)

- Humour, satire (popular, but rarely “awarded”)

The silent giant nobody admits is the base of the pyramid

- Educational publishing (textbooks, guides, exam prep)

Here’s the thing: India’s publishing economy is heavily shaped by education, with trade books being a smaller slice than people assume. EY-Parthenon notes that India is dominated by educational book publishing, with trade publishing comparatively small.

That one fact explains a lot: the entire trade ecosystem often behaves like a cultural wing attached to an education-first industry.

Why This Hierarchy Exists (It’s Not Just “Snobbery”)

People call it elitism and move on. That’s too easy. The hierarchy survives because it’s useful to multiple stakeholders.

Awards and institutions reward “difficulty”

Juries, academies, literary pages, and university syllabi tend to valorise complexity, innovation, social commentary, and stylistic seriousness. Poetry and literary fiction fit the criteria neatly. Romance and devotional retellings don’t, even if they carry cultural meaning.

Distribution systems privilege certain formats

The mass genres thrive where distribution is wide and fast: railway stalls, local shops, fairs, WhatsApp groups, cheap editions, subscription-like borrowing circles. Prestige genres thrive where discovery is curated: festivals, bookstores, reviews, and academic networks.

So it’s not just content. It’s a pipeline.

Class, caste, and “taste” are tangled together

In many language spheres, “serious literature” became associated with educated readerships and urban cultural capital. Popular fiction became associated with the masses—particularly lower-middle and working-class readers, who read for comfort, escape, momentum, devotion, and laughter.

And because India has never had a clean separation between class and “taste,” genre becomes a proxy for social signalling.

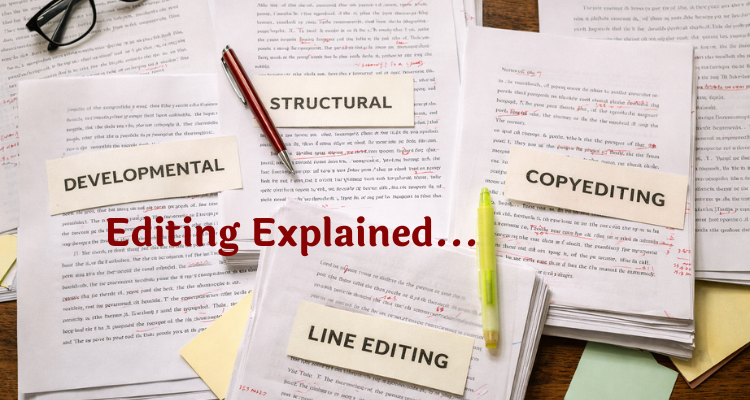

d) Editors are trained to think in terms of legitimacy

An editor who has grown up seeing “good books” as a certain kind of book will naturally believe that publishing romance is “not building the language.” That belief can be sincere—and still deeply unfair.

The Pulp Paradox: When Millions Read You, But Culture Pretends You Don’t Exist

If you want a clean example of the hierarchy’s hypocrisy, look at pulp fiction.

Hindi pulp authors have historically moved astonishing volumes. A Times of India report described top pulp writers selling in the hundreds of thousands, and cited Ved Prakash Sharma’s Vardi Wala Gunda as a landmark bestseller, with claims of extremely high cumulative sales over time.

Publishing Perspectives, while profiling Surender Mohan Pathak, notes that his books can sell more than 25,000 copies within six months of release—numbers most “serious” authors can only dream of.

And yet, in many literary circles, pulp remains something you “graduate from.”

What this really means is: we have a cultural system that respects difficulty more than reach. Which is odd, because language survives through reach.

If ten lakh readers are reading in Hindi, Marathi, Tamil, Bangla—fast, hungry, habitually—shouldn’t that be celebrated as language vitality?

But the hierarchy doesn’t measure vitality. It measures legitimacy.

Romance: The Biggest Genre Nobody Wants to Claim

In Indian languages, romance often travels under the rubrics of “family fiction,” “relationship stories,” “women’s reading,” “domestic novels,” or simply “popular fiction.” It sells because it deals in the real currency of everyday life: desire, negotiation, dignity, betrayal, recovery, hope.

But it’s frequently treated like a guilty pleasure, especially when written by women, for women.

This is a double hierarchy:

- Genre hierarchy (romance is “lesser”)

- Gender hierarchy (women’s reading is “lesser”)

You see it in cover design, marketing budgets, review attention, festival invites, and even in the way authors talk about their own work. Many romance writers quietly rebrand themselves as “social fiction” to gain entry into serious spaces, despite doing the same job: telling stories people actually finish.

Mythology and Devotion: Massive Readership, Uneasy Respect

Mythological retellings and devotional narratives are a giant engine in several language markets. They travel well across formats: print, audio, stage, television, and reels.

But their place in the hierarchy is unstable:

- If a myth retelling is framed as “research-based,” it climbs upward.

- If it is openly devotional, it can be dismissed as uncritical.

- If it is feminist/revisionist, it’s welcomed in elite spaces, but sometimes rejected by the traditional mass readership.

So the genre becomes a battleground for legitimacy from both sides.

This is also where language publishing intersects with politics and identity: who owns the “right” version of a story, who gets to reinterpret, and who gets to profit.

Children’s Books: Respect Without Revenue (Often)

Children’s publishing gets polite admiration. Everyone agrees it’s important. And then it’s underfunded.

Why? Children’s books require illustration, design, paper quality, careful editing, and strong distribution into schools and libraries. That’s expensive. Meanwhile, the market is distorted by education’s dominance; textbooks and guides take up oxygen, shelf space, and institutional attention.

This is the quiet tragedy: the genre that builds future readers is the one most likely to be treated as a “nice-to-have.”

Educational Publishing: The King That Doesn’t Attend the Party

If you want to understand power in Indian publishing, look away from literature festivals and toward the textbook economy.

A Printweek piece points out how NCERT and state textbook bodies dominate the textbook market and enjoy special protections, leaving limited room for private players.

And textbook piracy is not a small nuisance; it’s industrial. In January 2026, The Times of India reported a major NCERT-linked piracy raid seizing around 32,000 fake textbooks in Delhi/NCR.

Textbook money shapes everything:

- It funds printing capacity.

- It stabilises cash flows.

- It influences distributor relationships.

- It sets expectations for scale and margins.

So when trade publishers look down on mass genres, there’s a hidden irony: many of the same infrastructures that enable “serious literature” survive because of education-led economics.

The New Twist: Readers Are Changing Faster Than Gatekeepers

A few shifts are forcing the hierarchy to renegotiate.

Fiction momentum is rising in measured markets

NielsenIQ’s international book markets report for 2024 noted strong fiction growth across many territories, including a sharp increase in India (+30.7%).

Even if this doesn’t map perfectly oto every Indian-language segment, it signals something important: story consumption is accelerating, driven by pricing, discoverability, and new reader cohorts.

Audio is flattening the hierarchy

Audio doesn’t care about prestige the same way. A gripping romance, a thriller series, a myth retelling—these explode in audio because voice carries emotion and pace. In many Indian-language contexts, audio is elevating “low prestige” genres into high visibility.

Digital discovery rewards clarity, not gatekeeping

A reader searching “best Marathi crime thriller” or “Hindi romance novel recommendations” doesn’t arrive through juries. They arrive through communities, creators, and algorithms. This pushes publishers to market what readers ask for, not what institutions approve of.

Who Benefits From the Hierarchy?

Let’s be blunt.

- Elite institutions benefit because they maintain cultural authority.

- Some publishers benefit because prestige books build brand value even when sales are modest.

- Some authors benefit because legitimacy is a protective shield in a crowded marketplace.

- Readers don’t benefit—because their tastes are treated as less intelligent than they are.

- Languages don’t benefit—because restricting “seriousness” to a narrow band limits the living range of a language.

A language is not only its finest poems. It’s also its jokes, gossip, love letters, crime headlines, devotion, and late-night paperback thrillers. Cut out the mass shelf, and you amputate the daily life of the language.

So What Should Change?

This is where platforms like Rachnaye have a very practical role to play—not as moral judges of genre, but as infrastructure that treats all reading as legitimate.

Here are a few shifts that could genuinely soften the hierarchy:

Build recommendation systems that don’t privilege “prestige metadata.”

If readers love a genre, let discovery reflect that love....without apology.

Normalise “genre craft” conversations in Indian languages.

Workshops, editorial notes, and author interviews that treat romance plotting, thriller pacing, humorous timing, and myth retellings as serious craft.

Create parallel award ecosystems that reward reach and reader impact.

Not everything needs to mimic the Sahitya Akademi model. Some awards should measure readership, community building, and sustained series writing.

Invest in distribution and marketing for children’s books in Indian languages.

If you want language readership in 2036, this is where you bet.

Treat translations as bridges, not trophies.

Translate “prestige works,” yes. But also translate the best genre fiction across Indian languages, so a Bangla thriller can travel into Marathi, a Marathi romance into Tamil, and so on.

Add a comment

Add a comment