The Editor–Author Power Imbalance

December 17, 2025

The publishing world loves a comforting story: an editor “discovers” a manuscript, an author gets “guidance,” and a book emerges like a shared miracle.

That story exists. It’s also incomplete.

A more accurate description is messier: publishing runs on asymmetry.

Editors sit inside institutions—budgets, lists, sales meetings, reputational risk.

Authors, especially debut or midlist authors, sit outside—often emotionally invested, financially exposed, and dependent on a handful of decision-makers.

That gap—between institutional power and individual vulnerability—is the editor–author imbalance. It shapes what gets published, how books are edited, which voices are softened, and which disagreements are rebranded as “professional feedback.”

If we want a healthier Indian publishing ecosystem, we have to name how this imbalance works—from both sides.

Where the power actually sits

The editor’s power is not a villain’s power. It’s structural.

An editor controls (or strongly influences):

- Gatekeeping: what gets acquired, what gets rejected, what gets “maybe later.” The acquisition decision is rarely “editor alone”—it’s a cross-department negotiation where sales/marketing/PR weigh in.

- Framing: how a manuscript is described internally—its “comp titles,” its market positioning, the pitch that makes others say yes. Comp titles aren’t just marketing fluff; they’re decision tools.

- Timeline control: edits, proofs, cover copy deadlines, and—most crucially—how much time the author gets to think.

- Contract leverage (indirectly): editors aren’t the legal team, but editorial enthusiasm often decides how negotiable your terms are in practice.

Meanwhile, authors hold a different kind of power:

- The text itself: nobody can write the book but the author.

- Public voice: authors can bring readers, community credibility, and long-term brand value.

- Walking away: rare, but real—if an author has options (agented, proven audience, multiple offers), the balance shifts.

The imbalance is sharpest when authors have one offer, limited industry knowledge, and urgent personal stakes.

The “data layer” that quietly shifts power

One of the most significant changes in modern publishing is that editorial taste no longer operates in isolation. The room has numbers in it now—sometimes complex numbers, often proxy numbers.

Editors and publishers increasingly rely on:

- Sales history and comparable titles (comps)

Comps help publishers justify acquisition decisions, forecast sales, and align distribution expectations. But comps can also become a cage: if your book doesn’t resemble something

already proven, it is treated as “risk,” even when it’s brilliant.

- Acquisitions-meeting logic

In acquisitions, different departments effectively vote with their incentives: sales want predictability, marketing wants hooks, PR wants narratives, and finance wants margins. Editors can

love your book and still lose the room.

- Returns and reserves

The book trade’s returnability incentivises publishers to protect themselves through “reserve against returns,” which often means withholding a portion of royalties until the returns window

has closed. It’s not an Indian-only practice, but Indian authors feel it more because margins are thinner and payments are slower.

- Cost pressure and taxation realities

India-specific economic factors: input taxes on production and the GST treatment of royalties add friction to already tight Profit-and-Loss Statements.

What this “data layer” does to the relationship: it gives editors an apparently objective language—market fit, comps, projections—that can override an author’s lived truth. And it gives authors the sinking feeling that the book is being edited to satisfy a spreadsheet.

Sometimes it is.

Editorial bias: the part everyone knows and nobody likes to admit

Bias is not always conscious prejudice. Often, it’s “taste” and “experience” operating as shortcuts under pressure.

Editor-side biases (common patterns)

- Genre bias: certain genres are assumed to be “less serious” or harder to sell—romance, YA, speculative fiction in Indian settings, devotional writing unless it’s already celebrity-backed.

- Language/voice bias: “clean” English is rewarded; strongly regional cadence is often “smoothed.” This can erase cultural texture in the name of readability.

- Class/location bias: urban stories get treated as universal; non-metro stories are asked to “provide context.”

- Pedigree bias: the author bio matters more than editors admit—elite education, global publications, and known fellowships can create a presumption of competence and marketability.

- Ideological bias: some kinds of dissent are welcomed, others are labelled “too angry,” “not nuanced,” or “too risky”—which often means “this will cause internal trouble.”

This isn’t abstract; editors themselves talk about power dynamics in the profession and how authors perceive editors as gatekeepers.

Author-side biases (less discussed, equally real)

Authors carry biases too, especially in adversarial climates:

- Editors as enemies: Some authors assume every edit is a power play, not craft.

- Suspicion of “market talk”: authors may dismiss commercial constraints entirely, even when those constraints decide whether the book exists at all.

- Status anxiety: authors may overvalue external validation (e.g., prestige imprints, elite blurbers) and undervalue long-term editorial partnerships.

The worst outcomes happen when both sides treat the relationship as a courtroom rather than a workshop.

The dark mechanics of editing

Here are the truths that make writers angry—and editors defensive—because they’re often true.

“Tone” is a control lever.

Editors frequently request tone shifts: soften anger, reduce sarcasm, add “balance,” and remove “harshness.” Sometimes that improves craft. Sometimes it sanitises reality.

The dangerous part is when tone-policing is disguised as neutrality. It isn’t.

Time pressure is power

Editorial timelines can force authors into compliance: you can’t argue for a scene if you have 48 hours to turn around a structural edit while juggling a job and life.

Time becomes an invisible weapon, even when no one intends it.

The author’s vulnerability is often economic.

Many authors rely on advances, or on the credibility that publication unlocks (speaking gigs, fellowships, career transitions). Contract norms, royalty structures, and payment schedules can put authors in a long waiting game.

The editor may be kind. The system still isn’t.

Editors are not sovereign.

This is the editor’s uncomfortable truth: editors don’t always have the final say. Acquisitions are institutional. Marketing has veto power in practice. Sales projections can quietly kill beloved books.

So sometimes editors “push” authors not because they enjoy dominance, but because they’re translating institutional demands into manuscript-level changes.

What each side gets right

The editor’s best argument

A good editor represents the reader who isn’t inside the author’s head. Editing is, at its best, a professional act of attention—structure, clarity, rhythm, integrity.

Editors also see patterns across hundreds of books: what readers stumble on, what reviewers punish, what distribution realities demand. Acquisitions editors are often evaluated against acquisition goals and commercial outcomes—another pressure authors don’t always see.

The author’s best argument

A book is not a product spec. It is a lived experience shaped into language. Authors are not content vendors. They are the source of meaning.

When editorial interventions drift into cultural flattening, caste/class sanitisation, or forced universality, authors are right to resist. The “reader” an editor imagines is often narrower than the country the book comes from.

How to reduce the imbalance without romanticising either side

This is the practical heart of it.

What editors can do (that actually changes outcomes)

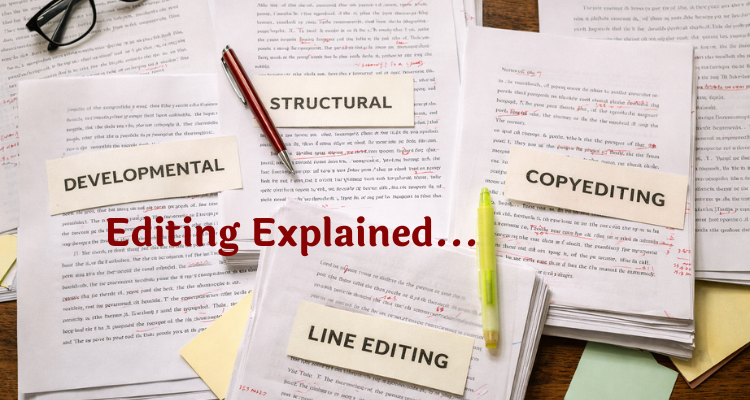

- Say what kind of edit this is. Structural? Line? Copy? “I want to change X because Y” is not optional; it’s respect.

- Name constraints honestly. If marketing needs a different position, I would say that. Don’t pretend it’s purely craft.

- Protect voice as a principle. Smoothness is not always an improvement.

- Build consent into the process. Authors should know which changes are negotiable and which are dealbreakers.

What authors can do (without becoming submissive)

- Ask for the editorial letter in writing and reply with your rationale, not emotion.

- Negotiate time, i.e. more time = more agency.

- Know standard contract traps (rights, royalty base, reserves, non-compete, reversion). “Reserve against returns” is common; understand what percentage and duration apply.

- Use a trusted second reader (agent, freelance editor, experienced peer) to separate ego-bruising from real craft issues.

- Protect one red-line principle (voice, politics, ending, narrator—choose one). If everything is negotiable, you’ll lose the book.

The uncomfortable conclusion

The editor–author relationship can be one of the most intellectually intimate collaborations in the creative economy. It can also become a subtle hierarchy in which “professionalism” is used to discipline authors and “art” to dismiss editors.

Both are convenient.

The imbalance doesn’t vanish through goodwill. It is reduced through transparency, shared language, and negotiated boundaries—and by acknowledging that data, bias, and institutional pressure are part of the room, whether we name them or not.

If Indian publishing wants better books, it needs better power hygiene.

Not politeness. Hygiene.

Add a comment

Add a comment