Resolve to Read

December 31, 2025

I am part of a book club WhatsApp group where people from across India discuss books throughout the year. I, too, chime in at times, not always,

Sharing a small snippet from the group, across the year. For anonymity purposes, naming the individuals as "someone"

Someone: "Ok, so you tell me, why do most Indians read foreign authors?"

Me: "Most Indians read foreign authors because English education, global validation (awards, adaptations), and aspirational reading culture make foreign books feel more 'worldly' and prestigious."

Someone: "Why do Indians prefer reading in English?"

Me: "English has historically been positioned as a language of mobility and status in India. Reading in English feels less like leisure and more like cultural capital."

Someone: "Don't you feel Indian authors are less creative than foreign authors?"

Me: "No, Never. Indian authors often write under social, historical, and political expectations, while foreign authors are freer to explore individualism and abstraction. The difference is context, not creativity."

Someone: "Should Indian readers read more Indian authors?"

Me: "Yes—not out of obligation, but because contemporary Indian writing offers humour, experimentation, and urban realities that global readers often miss."

Someone: "Can you tell me, how I Promised Myself Dostoevsky and Ended Up with Murakami Again?"

My response was just a smile...

Every New Year begins with a noble lie.

This year, it is whispered over filter coffee and WhatsApp forwards alike: “I will read more.”

Not just skim headlines. Not just hoard, unopened books like cultural insurance policies.

Proper reading. Page-turning. Bookmark-losing. Spine-cracking reading.

And inevitably, somewhere between the 2nd of January and the first work email, we join Goodreads.

Goodreads, that digital confessional where we publicly declare a goal—24 books this year!—and privately hope graphic novels count as literature. It gamifies virtue. It tracks our virtue. It reminds us, with quiet cruelty, that we are three books behind schedule while someone in Helsinki has already finished Tolstoy before breakfast.

Still, we persist. Because reading, like yoga and salads, feels morally superior even when poorly done.

Why the Indian Reader Reaches for an English Accent

Here’s the thing. When Indians resolve to read, they almost always resolve to read foreign authors—and almost always in English.

This is not accidental. This is conditioning.

English, for the Indian middle class, has long been marketed not as a language but as a lifestyle upgrade. Reading English books is not just consumption; it is aspiration. One does not merely read Orwell or Atwood—one participates in a global conversation, preferably while posting a photograph of the book next to a latte.

Indian authors, meanwhile, are often treated like distant relatives: respected, occasionally mentioned, but rarely invited home.

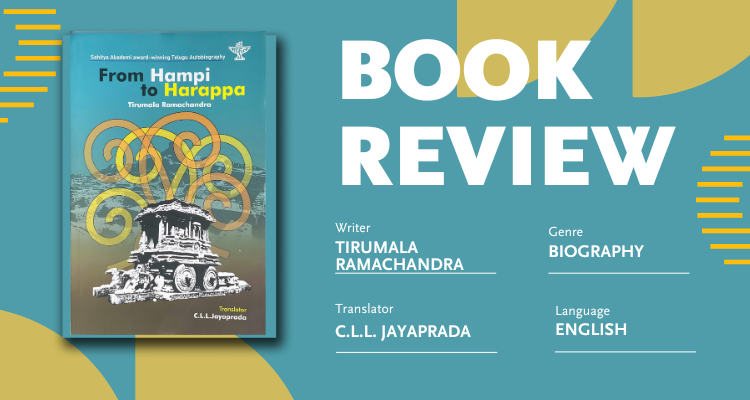

There’s also the ghost of the syllabus. Many of us first encountered Indian writing in school through grim excerpts that made India seem permanently miserable.

Caste. Poverty. Partition. Oppression. Important, yes—but hardly inviting when you’re sixteen and craving escape, not sociology.

So we flee. To Europe. To dystopias. To American small towns with charming bakeries and existential crises.

Foreign Authors Dream. Indian Authors Remember.

Let’s break this down.

Foreign authors—especially those who dominate Indian reading lists—often write about:

- Individual angst

- Personal freedom

- Existential dread with good furniture

- The self versus the system, preferably in metaphor

Indian authors, on the other hand, are frequently burdened with:

- History

- Society

- Family

- Caste, class, gender

- The system versus the self, loudly and directly

This difference is not about imagination. It’s about context.

A writer raised in relative social stability can afford to explore inner voids. A writer raised amid visible inequality is often compelled to explore outer fractures. When reality itself is dramatic, allegory feels indulgent.

Indian writing has often been expected to explain India—to outsiders, to elites, to history itself. Foreign writing, by contrast, is allowed to be simple.

The result? Indian books are seen as “serious.” Foreign books are seen as “fun.” One is assigned. The other is chosen.

Publishing, Prestige, and the Accent Bias

There’s also a quieter force at work: validation economics.

Foreign books arrive pre-approved—by Western prizes, international reviews, Netflix deals. Indian books, especially those in Indian languages, must prove themselves repeatedly, often in English translation, to be taken seriously by their own people.

Add to this the uneven marketing muscle, the limited shelf space for regional writing, and the dangerous myth that “Indian stories are all the same,” and you get a reading culture that mistakes familiarity for mediocrity.

Which is ironic, because no country produces novelty quite like India—only we hide it in languages we don’t promote.

The Goodreads Challenge and the Great Indian Reading Guilt

So what happens when the well-meaning Indian reader sets a Goodreads goal?

They load their list with Nobel winners, Booker shortlists, and Scandinavian crime. They feel cultured. They feel global. They also feel faintly dishonest when asked about Indian writers.

Somewhere around June, guilt creeps in. Should I read more Indian authors?

By July, the guilt is postponed. Next year, maybe.

This is not laziness. It is a habit.

And habits, like resolutions, don’t break unless we make them uncomfortable.

A Modest Proposal (With Apologies to Swift)

This New Year, instead of vowing to read more, try something more radical:

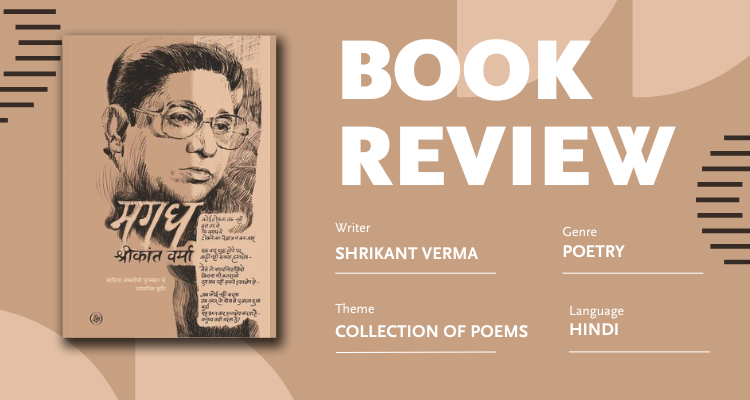

- Read one Indian author you’ve never heard of

- Read one book originally written in an Indian language.

- Read one Indian book that isn’t about suffering

Not because it’s patriotic. But because it’s refreshing.

Indian writing today is sharp, funny, romantic, experimental, urban, absurd, tender, and deeply aware of the world. It just doesn’t shout in a foreign accent.

The Real Resolution

Reading is not a race. Goodreads notwithstanding.

It is a conversation—with other minds, other lives, other realities. And if we keep outsourcing that conversation entirely, we shouldn’t be surprised when we struggle to hear ourselves.

So by all means, read Murakami. Read Ferrante. Read whoever keeps you awake at night.

But leave some space on that shelf—for voices that sound like the street outside your window.

You might discover that the most interesting foreign land you’ve ignored all along is your own.

Happy reading. And yes, graphic novels count.

Let me know what you finished in 2025 or will start in 2026?

Add a comment

Add a comment